Welcome to Swift

About Swift

Swift is a new programming language

for iOS and OS X apps that builds on the best of C and Objective-C, without the

constraints of C compatibility. Swift adopts safe programming patterns and adds

modern features to make programming easier, more flexible, and more fun.

Swift’s clean slate, backed by the mature and much-loved Cocoa and Cocoa Touch

frameworks, is an opportunity to reimagine how software development works.

Swift has been years in the making.

Apple laid the foundation for Swift by advancing our existing compiler,

debugger, and framework infrastructure. We simplified memory management with

Automatic Reference Counting (ARC). Our framework stack, built on the solid

base of Foundation and Cocoa, has been modernized and standardized throughout.

Objective-C itself has evolved to support blocks, collection literals, and

modules, enabling framework adoption of modern language technologies without

disruption. Thanks to this groundwork, we can now introduce a new language for

the future of Apple software development.

Swift feels familiar to Objective-C

developers. It adopts the readability of Objective-C’s named parameters and the

power of Objective-C’s dynamic object model. It provides seamless access to

existing Cocoa frameworks and mix-and-match interoperability with Objective-C

code. Building from this common ground, Swift introduces many new features and

unifies the procedural and object-oriented portions of the language.

Swift is friendly to new programmers. It is

the first industrial-quality systems programming language that is as expressive

and enjoyable as a scripting language. It supports playgrounds, an innovative

feature that allows programmers to experiment with Swift code and see the

results immediately, without the overhead of building and running an app.

Swift combines the best in

modern language thinking with wisdom from the wider Apple engineering culture.

The compiler is optimized for performance, and the language is optimized for

development, without compromising on either. It’s designed to scale from

“hello, world” to an entire operating

system. All this makes Swift a sound future investment for developers and for

Apple.

Swift is a fantastic way to write iOS and OS X apps, and

will continue to evolve with new features and capabilities. Our goals for Swift

are ambitious. We can’t wait to see what you create with it.

A Swift Tour

Tradition suggests that the first program

in a new language should print the words “Hello, world” on the screen. In

Swift, this can be done in a single line:

println("Hello, world")

If you have written code in C or

Objective-C, this syntax looks familiar to you—in Swift, this line of code is a

complete program. You don’t need to import a separate library for functionality

like input/output or string handling. Code written at global scope is used as

the entry point for the program, so you don’t need a main function. You also don’t need to write semicolons at the end of

every statement.

This tour gives you enough

information to start writing code in Swift by showing you how to accomplish a

variety of programming tasks. Don’t worry if you don’t understand

something—everything introduced in this tour is explained in detail in the rest

of this book.

NOTE

For the best experience, open this

chapter as a playground in Xcode. Playgrounds allow you to edit the code

listings and see the result immediately.

Simple Values

Use let to make a constant and var to make a variable. The value of a

constant doesn’t need to be known at compile time, but you must assign it a

value exactly once. This means you can use constants to name a value that you

determine once but use in many places.

var myVariable

= 42 myVariable

= 50 let

myConstant = 42

var myVariable

= 42 myVariable

= 50 let

myConstant = 42

A constant or variable must have the

same type as the value you want to assign to it.

However, you don’t always have to

write the type explicitly. Providing a value when you create a constant or

variable lets the compiler infer its type. In the example above, the compiler

infers that myVariable is an

integer because its initial value is a integer.

If the initial

value doesn’t provide enough information (or if there is no initial value),

specify the type by writing it after the variable, separated by a colon.

let implicitInteger

= 70 let

implicitDouble = 70.0 let explicitDouble: Double

= 70

let implicitInteger

= 70 let

implicitDouble = 70.0 let explicitDouble: Double

= 70

EXPERIMENT

Create a constant with an explicit

type of Float and a

value of 4.

Values are

never implicitly converted to another type. If you need to convert a value to a

different type, explicitly make an instance of the desired type.

let label

= "The width is " let width

= 94 let

widthLabel = label + String(width)

let label

= "The width is " let width

= 94 let

widthLabel = label + String(width)

EXPERIMENT

Try removing the conversion to String from the last line. What error do you get?

There’s an even

simpler way to include values in strings: Write the value in parentheses, and

write a backslash (\) before the

parentheses. For example:

let apples

= 3 let

oranges = 5 let appleSummary = "I

have \(apples) apples." let

fruitSummary = "I have \(apples

+ oranges) pieces of fruit."

let apples

= 3 let

oranges = 5 let appleSummary = "I

have \(apples) apples." let

fruitSummary = "I have \(apples

+ oranges) pieces of fruit."

EXPERIMENT

Use \()

to include a floating-point calculation in a string and to include someone’s

name in a greeting.

Create arrays

and dictionaries using brackets ([]), and access their elements by writing the index or key in

brackets.

var shoppingList

= ["catfish", "water", "tulips",

"blue paint"] shoppingList[1]

= "bottle of water"

var shoppingList

= ["catfish", "water", "tulips",

"blue paint"] shoppingList[1]

= "bottle of water"

var

occupations = [

"Malcolm":

"Captain",

"Kaylee":

"Mechanic",

] occupations["Jayne"]

= "Public Relations"

To create an

empty array or dictionary, use the initializer syntax.

let emptyArray

= String[]() let emptyDictionary

= Dictionary<String, Float>()

let emptyArray

= String[]() let emptyDictionary

= Dictionary<String, Float>()

If type information can be inferred, you can

write an empty array as [] and an empty dictionary as [:]—for example, when you set a new value for a variable or pass an

argument to a function.

shoppingList

= [] //

Went shopping and bought everything.

Control Flow

Use if and switch to make

conditionals, and use for-in, for, while, and do-while to make loops. Parentheses around the

condition or loop variable are optional. Braces around the body are required.

let individualScores

= [75, 43,

103, 87,

12] var

teamScore = 0 for score in

individualScores { if score

> 50 {

teamScore += 3

let individualScores

= [75, 43,

103, 87,

12] var

teamScore = 0 for score in

individualScores { if score

> 50 {

teamScore += 3

} else

{

teamScore += 1

}

}

}

Score

In an if statement, the conditional must be a Boolean expression—this means

that code such as if score { ... } is

an error, not an implicit comparison to zero.

You can use if and let together to

work with values that might be missing. These values are represented as

optionals. An optional value either contains a value or contains nil to indicate that the value is missing.

Write a question mark (?) after the type of a value to mark the value as optional.

var

optionalString: String? = "Hello"

optionalString == nil

var optionalName:

String? = "John

Appleseed" var greeting = "Hello!"

if let

name = optionalName

{ greeting = "Hello,

\(name)"

var optionalName:

String? = "John

Appleseed" var greeting = "Hello!"

if let

name = optionalName

{ greeting = "Hello,

\(name)"

}

EXPERIMENT

Change optionalName

to nil. What greeting do you get? Add an else clause that sets a different greeting if optionalName is nil.

If the optional value is nil, the conditional is false and the code in braces is skipped. Otherwise, the optional value is

unwrapped and assigned to the constant after let, which makes the unwrapped value available inside the block of

code.

Switches support any kind of data

and a wide variety of comparison operations—they aren’t limited to integers and

tests for equality.

let vegetable

= "red pepper" switch

vegetable { case "celery":

let vegetable

= "red pepper" switch

vegetable { case "celery":

let

vegetableComment = "Add some raisins and make ants on a log." case "cucumber",

"watercress":

let

vegetableComment = "That would make a good tea sandwich." case let

x where

x.hasSuffix("pepper"):

let

vegetableComment = "Is it a spicy \(x)?" default: vegetableComment

= "Everything tastes good in soup."

let

vegetableComment = "Is it a spicy \(x)?" default: vegetableComment

= "Everything tastes good in soup."

EXPERIMENT

Try removing the default case. What

error do you get?

After executing the code inside the switch case that

matched, the program exits from the switch statement. Execution doesn’t

continue to the next case, so there is no need to explicitly break out of the

switch at the end of each case’s code.

You use for-in to iterate over

items in a dictionary by providing a pair of names to use for each key-value

pair.

let interestingNumbers

= [

let interestingNumbers

= [

"Prime":

[2, 3,

5, 7,

11, 13],

"Fibonacci":

[1, 1,

2, 3,

5, 8],

"Square":

[1, 4,

9, 16,

25],

] var largest

= 0 for

(kind, numbers)

in interestingNumbers

{ for number

in numbers

{

if number

> largest { largest = number

}

t

EXPERIMENT

Add another variable to keep track

of which kind of number was the largest, as well as what that largest number

was.

Use while to repeat a block of code until a condition changes. The condition

of a loop can be at the end instead, ensuring that the loop is run at least

once.

var

n = 2

while n

< 100 { n = n

* 2

}

n

var m

= 2

var m

= 2

do

{ m = m

* 2 e

m < 100

You can keep an index in a

loop—either by using .. to make a range of indexes or by writing an explicit

initialization, condition, and increment. These two loops do the same thing:

var firstForLoop

= 0 for

i in

0..3

{ firstForLoop += i

var firstForLoop

= 0 for

i in

0..3

{ firstForLoop += i

} firstForLoop

var secondForLoop

= 0 for

var i

= 0; i

< 3; ++i

{ secondForLoop += 1

ndForLoop

ndForLoop

Use .. to make a range that omits its upper value, and use ... to make a range that includes both

values.

Functions and Closures

Use func to declare a function. Call a function by following its name with a

list of arguments in parentheses. Use -> to separate the parameter names and types from the function’s

return type.

func greet(name: String,

day: String)

-> String { return "Hello

\(name), today is \(day)."

func greet(name: String,

day: String)

-> String { return "Hello

\(name), today is \(day)."

}

greet("Bob",

"Tuesday")

EXPERIMENT

Remove the day

parameter. Add a parameter to include today’s lunch special in the greeting.

Use a tuple to return multiple

values from a function.

func getGasPrices()

-> (Double, Double,

Double) { return (3.59,

3.69, 3.79)

func getGasPrices()

-> (Double, Double,

Double) { return (3.59,

3.69, 3.79)

} getGasPrices()

Functions can also take a variable

number of arguments, collecting them into an array.

func sumOf(numbers: Int...)

-> Int { var sum

= 0 for number

in numbers

{

sum += number

func sumOf(numbers: Int...)

-> Int { var sum

= 0 for number

in numbers

{

sum += number

} return sum

}

sumOf() sumOf(42, 597,

12)

}

sumOf() sumOf(42, 597,

12)

EXPERIMENT

Write a function that calculates

the average of its arguments.

Functions can be

nested. Nested functions have access to variables that were declared in the

outer function. You can use nested functions to organize the code in a function

that is long or complex.

func returnFifteen()

-> Int { var y

= 10 func add()

{

y += 5

func returnFifteen()

-> Int { var y

= 10 func add()

{

y += 5

} add() return y

} returnFifteen()

Functions are a first-class type.

This means that a function can return another function as its value.

func makeIncrementer()

-> (Int -> Int) { func addOne(number: Int)

-> Int {

return 1

+ number

func makeIncrementer()

-> (Int -> Int) { func addOne(number: Int)

-> Int {

return 1

+ number

} return addOne

} var

increment = makeIncrementer()

increment(7)

increment(7)

A function can take another

function as one of its arguments.

func hasAnyMatches(list: Int[],

condition: Int -> Bool)

-> Bool { for item

in list

{

if condition(item) {

return true

func hasAnyMatches(list: Int[],

condition: Int -> Bool)

-> Bool { for item

in list

{

if condition(item) {

return true

} } return false

} func

lessThanTen(number: Int)

-> Bool { turn

number < 10

umbers

= [20, 19,

7, 12]

nyMatches(numbers, lessThanTen)

Functions are actually a special case of closures. You

can write a closure without a name by surrounding code with braces ({}). Use in to separate the arguments and return type from the body.

numbers.map({

(number:

Int) -> Int in let result

= 3 * number

return result

(number:

Int) -> Int in let result

= 3 * number

return result

})

EXPERIMENT

Rewrite the closure to return zero

for all odd numbers.

You have several options for

writing closures more concisely. When a closure’s type is already known, such

as the callback for a delegate, you can omit the type of its parameters, its

return type, or both. Single statement closures implicitly return the value of

their only statement. numbers.map({ number

in 3

* number })

You can refer to parameters by

number instead of by name—this approach is especially useful in very short

closures. A closure passed as the last argument to a function can appear

immediately after the parentheses.

sort([1, 5,

3, 12,

2]) { $0

> $1 }

Objects and Classes

Use class followed by the class’s name to create a class. A property

declaration in a class is written the same way as a constant or variable

declaration, except that it is in the context of a class. Likewise, method and

function declarations are written the same way.

class Shape

{ var numberOfSides

= 0 func simpleDescription()

-> String {

return "A

shape with \(numberOfSides) sides." }

class Shape

{ var numberOfSides

= 0 func simpleDescription()

-> String {

return "A

shape with \(numberOfSides) sides." }

}

EXPERIMENT

Add a constant property with let, and add another method that takes an argument.

Create an instance of a class by

putting parentheses after the class name. Use dot syntax to access the

properties and methods of the instance.

var shape

= Shape() shape.numberOfSides = 7

var shapeDescription

= shape.simpleDescription()

var shape

= Shape() shape.numberOfSides = 7

var shapeDescription

= shape.simpleDescription()

This version of the Shape class is missing something important:

an initializer to set up the class when an instance is created. Use init to create one.

class NamedShape

{ var numberOfSides:

Int = 0

var name:

String

class NamedShape

{ var numberOfSides:

Int = 0

var name:

String

init(name:

String) {

self.name

= name

}

func

simpleDescription() -> String { return

"A shape with \(numberOfSides)

sides."

Notice how self is used to distinguish the name property from the name argument to the initializer. The arguments to the initializer are

passed like a function call when you create an instance of the class. Every

property needs a value assigned—either in its declaration (as with numberOfSides) or in the initializer (as

with name).

Use deinit to create a deinitializer if you need to perform some cleanup

before the object is deallocated.

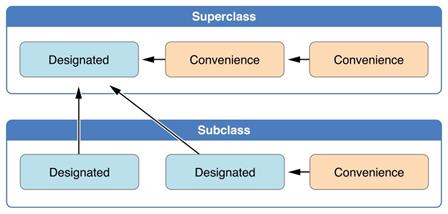

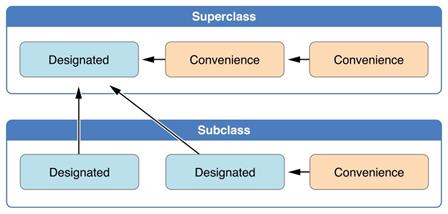

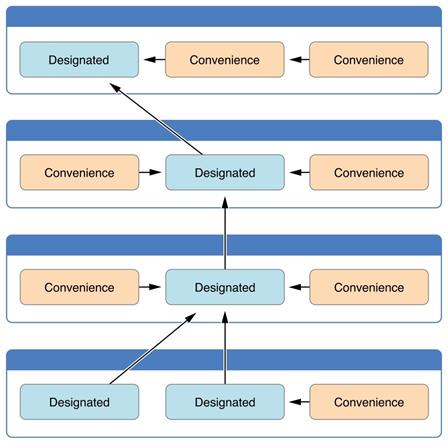

Subclasses include their superclass name

after their class name, separated by a colon. There is no requirement for

classes to subclass any standard root class, so you can include or omit a

superclass as needed.

Methods on a

subclass that override the superclass’s implementation are marked with override—overriding a method by accident,

without override, is

detected by the compiler as an error. The compiler also detects methods with override that don’t actually override any

method in the superclass.

class Square:

NamedShape { var sideLength:

Double

class Square:

NamedShape { var sideLength:

Double

init(sideLength: Double,

name: String)

{

self.sideLength

= sideLength

super.init(name: name)

numberOfSides = 4

}

nc area()

-> Double

{ return

sideLength * sideLength erride

func simpleDescription()

-> String { return

"A square with sides of length \(sideLength)."

st = Square(sideLength: 5.2,

name: "my

test square") rea()

impleDescription()

nc area()

-> Double

{ return

sideLength * sideLength erride

func simpleDescription()

-> String { return

"A square with sides of length \(sideLength)."

st = Square(sideLength: 5.2,

name: "my

test square") rea()

impleDescription()

EXPERIMENT

Make another subclass of NamedShape called Circle

that takes a radius and a name as arguments to its initializer. Implement an area and a describe

method on the Circle class.

In addition to

simple properties that are stored, properties can have a getter and a setter.

class

EquilateralTriangle: NamedShape { var sideLength:

Double = 0.0

init(sideLength: Double,

name: String)

{

self.sideLength

= sideLength super.init(name: name)

numberOfSides = 3

init(sideLength: Double,

name: String)

{

self.sideLength

= sideLength super.init(name: name)

numberOfSides = 3

}

r

perimeter: Double { t

{ return

3.0 * sideLength

t { sideLength = newValue

/ 3.0 erride

func simpleDescription()

-> String { return

"An equilateral triagle with sides of

length \(sideLength)." iangle

= EquilateralTriangle(sideLength: 3.1,

name: "a

triangle") le.perimeter le.perimeter

= 9.9 le.sideLength

t { sideLength = newValue

/ 3.0 erride

func simpleDescription()

-> String { return

"An equilateral triagle with sides of

length \(sideLength)." iangle

= EquilateralTriangle(sideLength: 3.1,

name: "a

triangle") le.perimeter le.perimeter

= 9.9 le.sideLength

In the setter for perimeter, the new value has the implicit

name newValue. You can provide

an explicit name in parentheses after set.

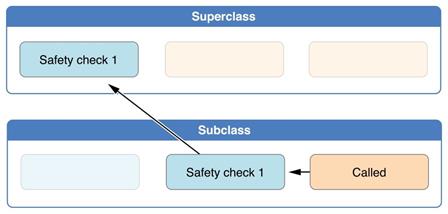

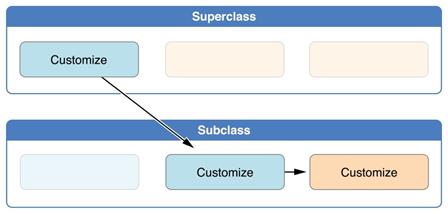

Notice that the initializer for the

EquilateralTriangle class

has three different steps:

1.

Setting the value of properties

that the subclass declares.

2.

Calling the superclass’s

initializer.

3.

Changing the value of

properties defined by the superclass. Any additional setup work that uses

methods, getters, or setters can also be done at this point.

If you don’t need to compute the

property but still need to provide code that is run before and after setting a

new value, use willSet and didSet. For example, the class below

ensures that the side length of its triangle is always the same as the side

length of its square.

class TriangleAndSquare

{ var triangle:

EquilateralTriangle { willSet {

class TriangleAndSquare

{ var triangle:

EquilateralTriangle { willSet {

square.sideLength

= newValue.sideLength

}

} var square:

Square {

willSet

{

triangle.sideLength = newValue.sideLength

(size: Double,

name: String)

{ square

= Square(sideLength:

size, name:

name) triangle

= EquilateralTriangle(sideLength: size,

name: name)

iangleAndSquare = TriangleAndSquare(size:

10, name:

"another test shape")

leAndSquare.square.sideLength

leAndSquare.triangle.sideLength leAndSquare.square

= Square(sideLength:

50, name:

"larger square")

leAndSquare.triangle.sideLength

(size: Double,

name: String)

{ square

= Square(sideLength:

size, name:

name) triangle

= EquilateralTriangle(sideLength: size,

name: name)

iangleAndSquare = TriangleAndSquare(size:

10, name:

"another test shape")

leAndSquare.square.sideLength

leAndSquare.triangle.sideLength leAndSquare.square

= Square(sideLength:

50, name:

"larger square")

leAndSquare.triangle.sideLength

Methods on classes have one

important difference from functions. Parameter names in functions are used only

within the function, but parameters names in methods are also used when you

call the method (except for the first parameter). By default, a method has the

same name for its parameters when you call it and within the method itself. You

can specify a second name, which is used inside the method.

class Counter

{ var count:

Int = 0

func incrementBy(amount: Int,

numberOfTimes times: Int)

{

count += amount

* times

class Counter

{ var count:

Int = 0

func incrementBy(amount: Int,

numberOfTimes times: Int)

{

count += amount

* times

}

} var

counter = Counter() counter.incrementBy(2,

numberOfTimes: 7)

When working with optional values, you can

write ? before operations like

methods, properties, and subscripting. If the value before the ? is nil, everything after the ? is ignored and the value of the whole expression is nil. Otherwise, the optional value is

unwrapped, and everything after the ? acts on the unwrapped value. In both cases, the value of the whole

expression is an optional value.

let optionalSquare:

Square? = Square(sideLength: 2.5,

name: "optional

square") let

sideLength = optionalSquare?.sideLength

let optionalSquare:

Square? = Square(sideLength: 2.5,

name: "optional

square") let

sideLength = optionalSquare?.sideLength

Enumerations and Structures

Use enum to create an enumeration. Like classes and all other named types,

enumerations can have methods associated with them.

enum Rank:

Int { case Ace

= 1 case Two,

Three, Four,

Five, Six,

Seven, Eight,

Nine, Ten

case Jack,

Queen, King

func simpleDescription()

-> String {

switch self

{

case .Ace:

enum Rank:

Int { case Ace

= 1 case Two,

Three, Four,

Five, Six,

Seven, Eight,

Nine, Ten

case Jack,

Queen, King

func simpleDescription()

-> String {

switch self

{

case .Ace:

return "ace"

case .Jack: return "jack"

case .Queen:

return "queen"

case .King:

return "king"

default:

return String(self.toRaw())

}

e = Rank.Ace eRawValue = ace.toRaw()

e = Rank.Ace eRawValue = ace.toRaw()

EXPERIMENT

Write a function that compares two Rank values by comparing their raw values.

In the example above, the raw

value type of the enumeration is Int, so you only have to specify the first raw value. The rest of the

raw values are assigned in order. You can also use strings or floating-point

numbers as the raw type of an enumeration.

Use the toRaw and fromRaw functions

to convert between the raw value and the enumeration value.

if let

convertedRank = Rank.fromRaw(3) { let threeDescription

= convertedRank.simpleDescription()

if let

convertedRank = Rank.fromRaw(3) { let threeDescription

= convertedRank.simpleDescription()

}

The member values of an enumeration are

actual values, not just another way of writing their raw values. In fact, in

cases where there isn’t a meaningful raw value, you don’t have to provide one.

enum Suit

{ case Spades,

Hearts, Diamonds,

Clubs func simpleDescription()

-> String {

switch self

{

case .Spades:

enum Suit

{ case Spades,

Hearts, Diamonds,

Clubs func simpleDescription()

-> String {

switch self

{

case .Spades:

return "spades"

case .Hearts:

return "hearts"

case .Diamonds: return "diamonds"

case .Clubs:

return "clubs"

}

arts = Suit.Hearts artsDescription = hearts.simpleDescription()

arts = Suit.Hearts artsDescription = hearts.simpleDescription()

EXPERIMENT

Add a color

method to Suit that

returns “black” for spades and clubs, and returns “red” for hearts and

diamonds.

Notice the two ways that the Hearts member of the enumeration is

referred to above: When assigning a value to the hearts constant, the enumeration member Suit.Hearts is referred to by its full name because the constant doesn’t have

an explicit type specified. Inside the switch, the enumeration is referred to

by the abbreviated form .Hearts because the value of self is already known to be a suit. You can use the abbreviated form

anytime the value’s type is already known.

Use struct to create a structure. Structures support many of the same

behaviors as classes, including methods and initializers. One of the most

important differences between structures and classes is that structures are

always copied when they are passed around in your code, but classes are passed

by reference.

struct Card

{ var rank:

Rank var suit:

Suit func simpleDescription()

-> String {

return "The

\(rank.simpleDescription())

of \(suit.simpleDescription())"

}

struct Card

{ var rank:

Rank var suit:

Suit func simpleDescription()

-> String {

return "The

\(rank.simpleDescription())

of \(suit.simpleDescription())"

}

}

let threeOfSpades

= Card(rank:

.Three, suit:

.Spades) let

threeOfSpadesDescription

= threeOfSpades.simpleDescription()

EXPERIMENT

Add a method to Card that creates a full deck of cards, with one card of

each combination of rank and suit.

An instance of an enumeration

member can have values associated with the instance. Instances of the same

enumeration member can have different values associated with them. You provide

the associated values when you create the instance. Associated values and raw

values are different: The raw value of an enumeration member is the same for

all of its instances, and you provide the raw value when you define the

enumeration.

For example, consider the case of requesting

the sunrise and sunset time from a server. The server either responds with the

information or it responds with some error information.

enum

ServerResponse {

case

Result(String,

String) case Error(String)

}

let

success = ServerResponse.Result("6:00 am", "8:09

pm") let

failure = ServerResponse.Error("Out of cheese.")

switch

success { let .Result(sunrise, sunset):

serverResponse

= "Sunrise is at \(sunrise)

and sunset is at \(sunset)." let

.Error(error): serverResponse

= "Failure... \(error)"

serverResponse

= "Sunrise is at \(sunrise)

and sunset is at \(sunset)." let

.Error(error): serverResponse

= "Failure... \(error)"

EXPERIMENT

Add a third case to ServerResponse and to the switch.

Notice how the sunrise and sunset

times are extracted from the ServerResponse value as part of matching the value against the switch cases.

Protocols and Extensions

Use protocol to declare a protocol.

protocol ExampleProtocol

{ var simpleDescription:

String { get

} mutating func

adjust()

protocol ExampleProtocol

{ var simpleDescription:

String { get

} mutating func

adjust()

}

Classes, enumerations, and structs

can all adopt protocols.

class SimpleClass:

ExampleProtocol { var simpleDescription:

String = "A

very simple class." var anotherProperty:

Int = 69105

func adjust()

{

simpleDescription += " Now 100%

adjusted."

class SimpleClass:

ExampleProtocol { var simpleDescription:

String = "A

very simple class." var anotherProperty:

Int = 69105

func adjust()

{

simpleDescription += " Now 100%

adjusted."

}

}

var

a = SimpleClass()

a.adjust()

Description

= a.simpleDescription

SimpleStructure:

ExampleProtocol { r simpleDescription:

String = "A

simple structure" utating

func adjust()

{ simpleDescription

+= " (adjusted)"

= SimpleStructure()

ust()

Description

= b.simpleDescription

EXPERIMENT

Write an enumeration that conforms

to this protocol.

Notice the use of the mutating keyword in the declaration of SimpleStructure to mark a method that

modifies the structure. The declaration of SimpleClass doesn’t need any of its methods marked as mutating because methods

on a class can always modify the class.

Use extension to add functionality to an existing type, such as new methods and

computed properties. You can use an extension to add protocol conformance to a

type that is declared elsewhere, or even to a type that you imported from a

library or framework.

extension Int:

ExampleProtocol { var simpleDescription:

String { return "The

number \(self)"

extension Int:

ExampleProtocol { var simpleDescription:

String { return "The

number \(self)"

} mutating func

adjust() {

self += 42

}

}

7.simpleDescription

EXPERIMENT

Write an extension for the Double type that adds an absoluteValue

property.

You can use a protocol name just

like any other named type—for example, to create a collection of objects that

have different types but that all conform to a single protocol. When you work

with values whose type is a protocol type, methods outside the protocol

definition are not available.

let protocolValue:

ExampleProtocol = a protocolValue.simpleDescription

let protocolValue:

ExampleProtocol = a protocolValue.simpleDescription

//

protocolValue.anotherProperty //

Uncomment to see the error

Even though the variable protocolValue has a runtime type of SimpleClass, the compiler treats it as the

given type of ExampleProtocol.

This means that you can’t accidentally access methods or properties that the

class implements in addition to its protocol conformance.

Generics

Write a name inside angle brackets

to make a generic function or type.

func repeat<ItemType>(item:

ItemType, times: Int)

-> ItemType[] { var result

= ItemType[]() for i

in 0..times {

result += item

func repeat<ItemType>(item:

ItemType, times: Int)

-> ItemType[] { var result

= ItemType[]() for i

in 0..times {

result += item

} return result

} repeat("knock",

4)

You can make generic forms of

functions and methods, as well as classes, enumerations, and structures.

// Reimplement the Swift standard library's optional type enum OptionalValue<T> { case None case Some(T)

// Reimplement the Swift standard library's optional type enum OptionalValue<T> { case None case Some(T)

}

var possibleInteger:

OptionalValue<Int> = .None possibleInteger

= .Some(100)

Use where after the type name to specify a list of requirements—for example,

to require the type to implement a protocol, to require two types to be the

same, or to require a class to have a particular superclass.

func anyCommonElements <T,

U where

T: Sequence,

U: Sequence,

T.GeneratorType.Element: Equatable,

T.GeneratorType.Element

== U.GeneratorType.Element> (lhs:

T, rhs:

U) -> Bool

{

for

lhsItem in lhs

{

for rhsItem

in rhs

{

if lhsItem

== rhsItem {

return true

for

lhsItem in lhs

{

for rhsItem

in rhs

{

if lhsItem

== rhsItem {

return true

}

}

} return false

} return false

ommonElements([1, 2,

3], [3])

EXPERIMENT

Modify the anyCommonElements

function to make a function that returns an array of the elements that any two

sequences have in common.

In the simple

cases, you can omit where and simply

write the protocol or class name after a colon. Writing <T: Equatable> is the same as writing

<T where T: Equatable>.

Language Guide

The Basics

Swift is a new programming

language for iOS and OS X app development. Nonetheless, many parts of Swift

will be familiar from your experience of developing in C and Objective-C.

Swift provides its own versions of

all fundamental C and Objective-C types, including Int

for integers; Double and Float for

floating-point values; Bool for Boolean values; and String for textual data. Swift also provides powerful versions of the two

primary collection types, Array and Dictionary, as

described in Collection Types.

Like C, Swift uses variables to

store and refer to values by an identifying name. Swift also makes extensive

use of variables whose values cannot be changed. These are known as constants,

and are much more powerful than constants in C. Constants are used throughout

Swift to make code safer and clearer in intent when you work with values that

do not need to change.

In addition to familiar types,

Swift introduces advanced types not found in Objective-C. These include tuples,

which enable you to create and pass around groupings of values. Tuples can

return multiple values from a function as a single compound value.

Swift also introduces optional types,

which handle the absence of a value. Optionals say either “there is a value,

and it equals x” or “there isn’t a value at all”. Optionals are similar to

using nil with pointers in

Objective-C, but they work for any type, not just classes. Optionals are safer

and more expressive than nil pointers in Objective-C and are at the heart of many of Swift’s

most powerful features.

Optionals are an example of the

fact that Swift is a type safe language. Swift helps you to be clear about the

types of values your code can work with. If part of your code expects a String, type safety prevents you from

passing it an Int by mistake.

This enables you to catch and fix errors as early as possible in the

development process.

Constants and Variables

Constants and variables associate a name (such as maximumNumberOfLoginAttempts or welcomeMessage) with a value of a

particular type (such as the number 10 or the string "Hello"). The value of a constant cannot be changed once it is set, whereas

a variable can be set to a different value in the future.

Declaring Constants and

Variables

Constants and variables must be

declared before they are used. You declare constants with the let keyword and variables with the var keyword. Here’s an example of how

constants and variables can be used to track the number of login attempts a

user has made:

let maximumNumberOfLoginAttempts

= 10 var

currentLoginAttempt = 0

let maximumNumberOfLoginAttempts

= 10 var

currentLoginAttempt = 0

This code can be read as:

“Declare a new constant called maximumNumberOfLoginAttempts, and give it a

value of 10. Then, declare a

new variable called currentLoginAttempt,

and give it an initial value of 0.”

In this example, the maximum number of

allowed login attempts is declared as a constant, because the maximum value

never changes. The current login attempt counter is declared as a variable,

because this value must be incremented after each failed login attempt.

You can declare multiple constants

or multiple variables on a single line, separated by commas:

var

x = 0.0,

y = 0.0,

z = 0.0

NOTE

If a stored value in your code is

not going to change, always declare it as a constant with the let keyword. Use variables only for storing values that

need to be able to change.

Type Annotations

You can provide a type annotation when you

declare a constant or variable, to be clear about the kind of values the

constant or variable can store. Write a type annotation by placing a colon

after the constant or variable name, followed by a space, followed by the name

of the type to use.

This example provides a type

annotation for a variable called welcomeMessage, to indicate that the variable can store String values:

var

welcomeMessage: String

The colon in the declaration means

“…of type…,” so the code above can be read as:

“Declare a variable called welcomeMessage that is of type String.”

The phrase “of type String” means “can store any String value.” Think of it as meaning “the

type of thing” (or “the kind of thing”) that can be stored.

The welcomeMessage variable can now be set to any string value without error:

welcomeMessage

= "Hello"

NOTE

It

is rare that you need to write type annotations in practice. If you provide an

initial value for a constant or variable at the point that it is defined, Swift

can almost always infer the type to be used for that constant or variable, as

described in Type

Safety and Type Inference. In the welcomeMessage

example above, no initial value is provided, and so the type of the welcomeMessage variable is specified with a type

annotation rather than being inferred from an initial value.

Naming Constants and Variables

You can use almost any character

you like for constant and variable names, including Unicode characters:

let

π = 3.14159

let 你好

= "你好世界" let = "dogcow"

let 你好

= "你好世界" let = "dogcow"

Constant and variable names cannot

contain mathematical symbols, arrows, private-use (or invalid) Unicode code

points, or line- and box-drawing characters. Nor can they begin with a number,

although numbers may be included elsewhere within the name.

Once you’ve declared a constant or variable of a certain

type, you can’t redeclare it again with the same name, or change it to store

values of a different type. Nor can you change a constant into a variable or a

variable into a constant.

NOTE

If

you need to give a constant or variable the same name as a reserved Swift

keyword, you can do so by surrounding the keyword with back ticks (`) when using it as a name. However, you should avoid

using keywords as names unless you have absolutely no choice.

You can change the value of an existing

variable to another value of a compatible type. In this example, the value of friendlyWelcome is changed from "Hello!" to "Bonjour!":

var friendlyWelcome

= "Hello!" friendlyWelcome

= "Bonjour!"

var friendlyWelcome

= "Hello!" friendlyWelcome

= "Bonjour!"

//

friendlyWelcome is now "Bonjour!"

Unlike a variable, the value of a

constant cannot be changed once it is set. Attempting to do so is reported as

an error when your code is compiled:

let languageName

= "Swift" languageName

= "Swift++"

let languageName

= "Swift" languageName

= "Swift++"

// this is a

compile-time error - languageName cannot be changed

Printing Constants and

Variables

You can print the current value of

a constant or variable with the println function:

println(friendlyWelcome)

// prints

"Bonjour!"

println is a global function that prints a value, followed by a line break,

to an appropriate output. If you are working in Xcode, for example, println prints its output in Xcode’s

“console” pane. (A second

function, print, performs the

same task without appending a line break to the end of the value to be

printed.)

The println function prints any String value you pass to it:

println("This is a string")

// prints

"This is a string"

The println function can print more complex logging messages, in a similar

manner to Cocoa’s NSLog function.

These messages can include the current values of constants and variables.

Swift uses string interpolation to

include the name of a constant or variable as a placeholder in a longer string,

and to prompt Swift to replace it with the current value of that constant or

variable. Wrap the name in parentheses and escape it with a backslash before

the opening parenthesis:

println("The current value of friendlyWelcome is \(friendlyWelcome)")

// prints "The current value of

friendlyWelcome is Bonjour!"

NOTE

All options you can use with string

interpolation are described in String Interpolation.

Comments

Use comments to include

non-executable text in your code, as a note or reminder to yourself. Comments

are ignored by the Swift compiler when your code is compiled.

Comments in Swift are very similar

to comments in C. Single-line comments begin with two forward-slashes (//):

// this is a

comment

You can also write multiline

comments, which start with a forward-slash followed by an asterisk (/*) and end with an asterisk followed by a

forward-slash (*/):

/* this is also a

comment, but written over multiple lines */

Unlike multiline comments in C,

multiline comments in Swift can be nested inside other multiline comments. You

write nested comments by starting a multiline comment block and then starting a

second multiline comment within the first block. The second block is then

closed, followed by the first block:

/* this is the start

of the first multiline comment /* this is the second, nested multiline comment

*/ this is the end of the first multiline comment */

Nested multiline comments enable

you to comment out large blocks of code quickly and easily, even if the code

already contains multiline comments.

Semicolons

Unlike many other languages, Swift does not

require you to write a semicolon (;) after each statement in your code, although you can do so if you

wish. Semicolons are required, however, if you want to write multiple separate

statements on a single line:

let

cat = " ";

println(cat)

// prints " "

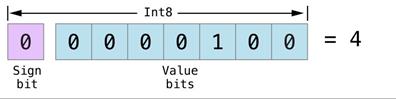

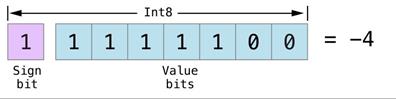

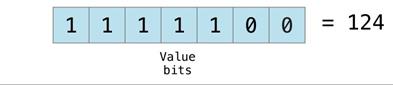

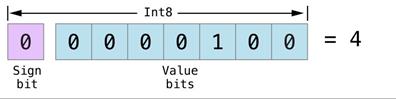

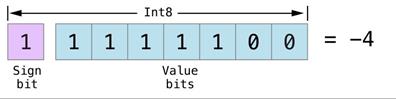

Integers

Integers are whole numbers with no

fractional component, such as 42 and -23. Integers are

either signed (positive, zero, or negative) or unsigned (positive or zero).

Swift provides signed and unsigned

integers in 8, 16, 32, and 64 bit forms. These integers follow a naming

convention similar to C, in that an 8-bit unsigned integer is of type UInt8, and a 32-bit signed integer is of

type Int32. Like all types in

Swift, these integer types have capitalized names.

Integer Bounds

You can access the minimum and

maximum values of each integer type with its min and max properties:

let

minValue = UInt8.min //

minValue is equal to 0, and is of type UInt8 let

maxValue = UInt8.max //

maxValue is equal to 255, and is of type UInt8

The values of these properties are of the

appropriate-sized number type (such as UInt8 in the example above) and can therefore be used in expressions

alongside other values of the same type.

Int

In most cases, you don’t need to pick a specific size of

integer to use in your code. Swift provides an additional integer type, Int, which has the same size as the current

platform’s native word size:

Unless you need to work with a

specific size of integer, always use Int for integer values in your code. This aids code consistency and

interoperability. Even on 32-bit platforms, Int

can store any value between -2,147,483,648 and 2,147,483,647, and

is large enough for many integer ranges.

UInt

Swift also provides an unsigned

integer type, UInt, which has the

same size as the current platform’s native word size:

NOTE

Use UInt

only when you specifically need an unsigned integer type with the same size as

the platform’s native word size. If this is not the case, Int is preferred, even when the values to be stored are

known to be nonnegative. A consistent use of Int

for integer values aids code interoperability, avoids the need to convert

between different number types, and matches integer type inference, as

described in Type

Safety and Type Inference.

Floating-Point Numbers

Floating-point numbers are numbers

with a fractional component, such as 3.14159, 0.1, and

-273.15.

Floating-point types can represent

a much wider range of values than integer types, and can store numbers that are

much larger or smaller than can be stored in an Int. Swift provides two signed floating-point number types:

NOTE

Double has a precision of at least 15 decimal digits, whereas

the precision of Float can be as

little as 6 decimal digits. The appropriate floating-point type to use depends

on the nature and range of values you need to work with in your code.

Type Safety and Type Inference

Swift is a type safe language. A type safe language

encourages you to be clear about the types of values your code can work with.

If part of your code expects a String, you can’t pass it an Int by mistake.

Because Swift is type safe, it performs type

checks when compiling your code and flags any mismatched types as errors. This

enables you to catch and fix errors as early as possible in the development

process.

Type-checking helps you avoid

errors when you’re working with different types of values. However, this

doesn’t mean that you have to specify the type of every constant and variable

that you declare. If you don’t specify the type of value you need, Swift uses

type inference to work out the appropriate type. Type inference enables a

compiler to deduce the type of a particular expression automatically when it

compiles your code, simply by examining the values you provide.

Because of type inference, Swift

requires far fewer type declarations than languages such as C or Objective-C. Constants

and variables are still explicitly typed, but much of the work of specifying

their type is done for you.

Type inference is particularly useful when you declare a

constant or variable with an initial value. This is often done by assigning a

literal value (or literal) to the constant or variable at the point that you

declare it. (A literal value is a value that appears directly in your source

code, such as 42 and 3.14159 in the examples below.)

For example, if you assign a

literal value of 42 to a new

constant without saying what type it is, Swift infers that you want the

constant to be an Int, because you

have initialized it with a number that looks like an integer:

let

meaningOfLife = 42

//

meaningOfLife is inferred to be of type Int

Likewise, if you don’t specify a

type for a floating-point literal, Swift infers that you want to create a Double:

let

pi = 3.14159

// pi is

inferred to be of type Double

Swift always chooses Double (rather than Float) when inferring the type of

floating-point numbers.

If you combine integer and

floating-point literals in an expression, a type of Double will be inferred from the context:

let

anotherPi = 3 + 0.14159

// anotherPi

is also inferred to be of type Double

The literal value of 3 has no explicit type in and of itself,

and so an appropriate output type of Double is inferred from the presence of a floating-point literal as part

of the addition.

Numeric Literals

Integer literals can be written

as:

All of these integer literals have

a decimal value of 17:

let

decimalInteger = 17 let binaryInteger = 0b10001 // 17 in binary notation let

octalInteger = 0o21

// 17 in octal notation let hexadecimalInteger

= 0x11 // 17 in hexadecimal notation

Floating-point literals can be

decimal (with no prefix), or hexadecimal (with a 0x prefix). They must always have a number (or hexadecimal number) on

both sides of the decimal point. They can also have an optional exponent,

indicated by an uppercase or lowercase e

for decimal floats, or an uppercase or lowercase p for hexadecimal floats.

For decimal numbers with an

exponent of exp, the base

number is multiplied by 10exp:

For hexadecimal numbers with an

exponent of exp, the base

number is multiplied by 2exp:

All of these floating-point

literals have a decimal value of 12.1875:

let

decimalDouble = 12.1875 let

exponentDouble = 1.21875e1 let

hexadecimalDouble = 0xC.3p0

Numeric literals can contain extra

formatting to make them easier to read. Both integers and floats can be padded

with extra zeroes and can contain underscores to help with readability. Neither

type of formatting affects the underlying value of the literal:

let

paddedDouble = 000123.456 let

oneMillion = 1_000_000 let

justOverOneMillion = 1_000_000.000_000_1

Numeric Type Conversion

Use the Int type for all general-purpose integer constants and variables in

your code, even if they are known to be non-negative. Using the default integer

type in everyday situations means that integer constants and variables are

immediately interoperable in your code and will match the inferred type for

integer literal values.

Use other integer types only when

they are are specifically needed for the task at hand, because of

explicitly-sized data from an external source, or for performance, memory

usage, or other necessary optimization. Using explicitly-sized types in these

situations helps to catch any accidental value overflows and implicitly

documents the nature of the data being used.

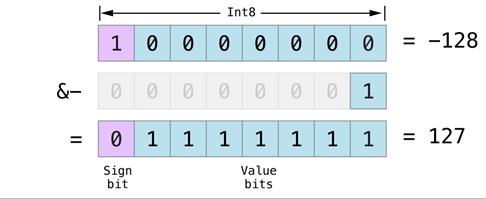

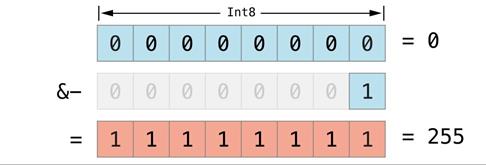

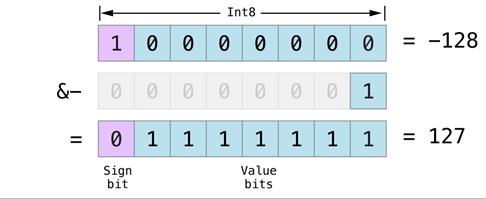

Integer Conversion

The range of numbers that can be

stored in an integer constant or variable is different for each numeric type.

An Int8 constant or variable

can store numbers between -128 and 127, whereas a UInt8 constant or variable can store

numbers between 0 and 255. A number that will not fit into a

constant or variable of a sized integer type is reported as an error when your

code is compiled:

let

cannotBeNegative: UInt8 = -1

// UInt8 cannot store

negative numbers, and so this will report an error let

tooBig: Int8

= Int8.max

+ 1

// Int8 cannot

store a number larger than its maximum value,

// and so this

will also report an error

Because each numeric type can store a

different range of values, you must opt in to numeric type conversion on a

case-by-case basis. This opt-in approach prevents hidden conversion errors and

helps make type conversion intentions explicit in your code.

To convert one specific number type

to another, you initialize a new number of the desired type with the existing

value. In the example below, the constant twoThousand is of type UInt16, whereas the constant one is of type UInt8. They cannot be added together directly, because they are not of

the same type. Instead, this example calls UInt16(one) to create a new UInt16 initialized with the value of one, and uses this value in place of the original:

let

twoThousand: UInt16 = 2_000

let one:

UInt8 = 1

let twoThousandAndOne

= twoThousand + UInt16(one)

Because both sides of the addition

are now of type UInt16, the

addition is allowed. The output constant (twoThousandAndOne) is inferred to be of type UInt16, because it is the sum of two UInt16 values.

SomeType(ofInitialValue) is the default way to call the initializer of a Swift type and pass

in an initial value. Behind the scenes, UInt16 has an initializer that accepts a UInt8 value, and so this initializer is used to make a new UInt16 from an existing UInt8. You can’t pass in any type here,

however—it has to be a type for which UInt16 provides an initializer. Extending existing types to provide

initializers that accept new types (including your own type definitions) is

covered in Extensions.

Integer and Floating-Point

Conversion

Conversions between integer and

floating-point numeric types must be made explicit:

let

three = 3

let pointOneFourOneFiveNine

= 0.14159 let

pi = Double(three) + pointOneFourOneFiveNine

// pi equals

3.14159, and is inferred to be of type Double

Here, the value of the constant three is used to create a new value of type

Double, so that both sides

of the addition are of the same type. Without this conversion in place, the

addition would not be allowed.

The reverse is also true for

floating-point to integer conversion, in that an integer type can be

initialized with a Double or Float value:

let

integerPi = Int(pi)

// integerPi

equals 3, and is inferred to be of type Int

Floating-point values are always

truncated when used to initialize a new integer value in this way. This means

that 4.75 becomes 4, and -3.9 becomes -3.

NOTE

The rules for combining numeric

constants and variables are different from the rules for numeric literals. The

literal value 3 can be added directly to

the literal value 0.14159, because

number literals do not have an explicit type in and of themselves. Their type

is inferred only at the point that they are evaluated by the compiler.

Type Aliases

Type aliases define an alternative

name for an existing type. You define type aliases with the typealias keyword.

Type aliases are useful when you

want to refer to an existing type by a name that is contextually more

appropriate, such as when working with data of a specific size from an external

source:

typealias

AudioSample = UInt16

Once you define a type alias, you

can use the alias anywhere you might use the original name:

var

maxAmplitudeFound = AudioSample.min

//

maxAmplitudeFound is now 0

Here, AudioSample is defined as an alias for UInt16. Because it is an alias, the call to AudioSample.min actually calls UInt16.min, which provides an initial value of 0 for the maxAmplitudeFound

variable.

Booleans

Swift has a basic Boolean type,

called Bool. Boolean values are

referred to as logical, because they can only ever be true or false. Swift

provides two Boolean constant values, true and false:

let

orangesAreOrange = true let turnipsAreDelicious = false

The types of orangesAreOrange and turnipsAreDelicious

have been inferred as Bool from the fact that they were initialized with Boolean literal

values. As with Int and Double above, you don’t need to declare

constants or variables as Bool if you set them to true or false as soon as

you create them. Type inference helps make Swift code more concise and readable

when it initializes constants or variables with other values whose type is

already known.

Boolean values are particularly

useful when you work with conditional statements such as the if statement:

if

turnipsAreDelicious { println("Mmm,

tasty turnips!")

} else { println("Eww,

turnips are horrible.")

}

// prints

"Eww, turnips are horrible."

Conditional statements such as the if statement are covered in more detail in Control

Flow.

Swift’s type safety prevents

non-Boolean values from being be substituted for Bool. The following example reports a compile-time error:

let

i = 1

if

i {

//

this example will not compile, and will report an error

}

However, the alternative example

below is valid:

let

i = 1

if i

== 1 {

//

this example will compile successfully

}

The result of the i == 1 comparison is of type Bool, and so this second example passes the

type-check. Comparisons like i == 1 are discussed in Basic Operators.

As with other examples of type

safety in Swift, this approach avoids accidental errors and ensures that the

intention of a particular section of code is always clear.

Tuples

Tuples group multiple values into

a single compound value. The values within a tuple can be of any type and do

not have to be of the same type as each other.

In this example, (404, "Not Found") is a tuple

that describes an HTTP status code. An HTTP status code is a special value

returned by a web server whenever you request a web page. A status code of 404 Not Found is returned if you request a

webpage that doesn’t exist.

let

http404Error = (404, "Not Found")

//

http404Error is of type (Int, String), and equals (404, "Not Found")

The (404,

"Not Found") tuple groups together an Int and a String to give the HTTP status code two separate values: a number and a

human-readable description. It can be described as

“a tuple of type (Int, String)”.

You can create tuples from any

permutation of types, and they can contain as many different types as you like.

There’s nothing stopping you from having a tuple of type (Int, Int, Int), or (String, Bool), or indeed any other permutation

you require.

You can decompose a tuple’s

contents into separate constants or variables, which you then access as usual:

let

(statusCode, statusMessage) = http404Error

println("The status code is \(statusCode)")

// prints "The status code is 404" println("The

status message is \(statusMessage)")

// prints

"The status message is Not Found"

If you only need some of the

tuple’s values, ignore parts of the tuple with an underscore (_) when you decompose the tuple:

let

(justTheStatusCode, _) = http404Error println("The status code is \(justTheStatusCode)")

// prints

"The status code is 404"

Alternatively, access the

individual element values in a tuple using index numbers starting at zero:

println("The status code is \(http404Error.0)")

// prints "The

status code is 404" println("The status message is \(http404Error.1)")

// prints

"The status message is Not Found"

You can name the individual

elements in a tuple when the tuple is defined:

let

http200Status = (statusCode: 200,

description: "OK")

If you name the elements in a

tuple, you can use the element names to access the values of those elements:

println("The status code is \(http200Status.statusCode)")

// prints "The

status code is 200" println("The status message is \(http200Status.description)") //

prints "The status message is OK"

Tuples are particularly useful as

the return values of functions. A function that tries to retrieve a web page

might return the (Int, String) tuple

type to describe the success or failure of the page retrieval. By returning a

tuple with two distinct values, each of a different type, the function provides

more useful information about its outcome than if it could only return a single

value of a single type. For more information, see Functions with Multiple Return

Values.

NOTE

Tuples are useful for temporary

groups of related values. They are not suited to the creation of complex data

structures. If your data structure is likely to persist beyond a temporary

scope, model it as a class or structure, rather than as a tuple. For more

information, see Classes

and Structures.

Optionals

You use optionals

in situations where a value may be absent. An optional says: or

NOTE

The concept of optionals doesn’t

exist in C or Objective-C. The nearest thing in Objective-C is the ability to

return nil from a method that would otherwise

return an object, with nil

meaning “the absence of a valid object.” However, this only works for

objects—it doesn’t work for structs, basic C types, or enumeration values. For

these types, Objective-C methods typically return a special value (such as NSNotFound) to indicate the absence of a

value. This approach assumes that the method’s caller knows there is a special

value to test against and remembers to check for it. Swift’s optionals let you

indicate the absence of a value for any type at all, without the need for

special constants.

Here’s an

example. Swift’s String type has a

method called toInt, which tries

to convert a String value into

an Int value. However, not

every string can be converted into an integer.

The string "123" can be converted into the numeric value 123, but the string "hello, world" does not have an obvious numeric value to convert to.

The example below uses the toInt method to try to convert a String into an Int:

let

possibleNumber = "123" let

convertedNumber = possibleNumber.toInt()

//

convertedNumber is inferred to be of type "Int?", or "optional

Int"

Because the toInt method might fail, it returns an

optional Int, rather than an

Int. An optional Int is written as Int?, not Int. The question

mark indicates that the value it contains is optional, meaning that it might

contain some Int value, or it

might contain no value at all. (It can’t contain anything else, such as a Bool value or a String value. It’s either an Int, or it’s nothing at all.)

If Statements and Forced

Unwrapping

You can use an if statement to find out whether an optional contains a value. If an

optional does have a value, it evaluates to true; if it has no value at all, it evaluates to false.

Once you’re sure that the optional does

contain a value, you can access its underlying value by adding an exclamation

mark (!) to the end of the

optional’s name. The exclamation mark effectively says, “I know that this

optional definitely has a value; please use it.” This is known as forced

unwrapping of the optional’s value:

if

convertedNumber { println("\(possibleNumber)

has an integer value of \(convertedNumber!)")

} else

{ println("\(possibleNumber)

could not be converted to an integer") }

// prints

"123 has an integer value of 123"

For more on the if statement, see Control

Flow.

NOTE

Trying to use ! to access a non-existent optional value triggers a

runtime error. Always make sure that an optional contains a non-nil value before using !

to force-unwrap its value.

Optional Binding

You use optional binding to find out whether

an optional contains a value, and if so, to make that value available as a

temporary constant or variable. Optional binding can be used with if and while statements to check for a value inside an optional, and to extract

that value into a constant or variable, as part of a single action. if and while statements are described in more detail in Control

Flow.

Write optional bindings for the if statement as follows:

}

You can rewrite the possibleNumber example from above to use

optional binding rather than forced unwrapping:

if

let actualNumber

= possibleNumber.toInt() { println("\(possibleNumber)

has an integer value of \(actualNumber)")

} else

{ println("\(possibleNumber)

could not be converted to an integer") }

// prints

"123 has an integer value of 123"

This can be read as:

“If the optional Int returned by possibleNumber.toInt contains a value, set a new constant called actualNumber to the value contained in the

optional.”

If the conversion is successful, the actualNumber constant becomes available for

use within the first branch of the if statement. It has already been initialized with the value contained

within the optional, and so there is no need to use the ! suffix to access its value. In this

example, actualNumber is

simply used to print the result of the conversion.

You can use both constants and variables

with optional binding. If you wanted to manipulate the value of actualNumber within the first branch of the

if statement, you could

write if var actualNumber

instead, and the value contained within the optional would be made available as

a variable rather than a constant.

nil

You set an optional variable to a

valueless state by assigning it the special value nil:

var

serverResponseCode: Int? = 404

// serverResponseCode

contains an actual Int value of 404 serverResponseCode

= nil

//

serverResponseCode now contains no value

NOTE

nil

cannot be used with non-optional constants and variables. If a constant or

variable in your code needs to be able to cope with the absence of a value

under certain conditions, always declare it as an optional value of the

appropriate type.

If you define an optional constant

or variable without providing a default value, the constant or variable is

automatically set to nil for you:

var

surveyAnswer: String?

//

surveyAnswer is automatically set to nil

NOTE

Swift’s nil

is not the same as nil in

Objective-C. In Objective-C, nil

is a pointer to a non-existent object. In Swift, nil

is not a pointer—it is the absence of a value of a certain type. Optionals of

any type can be set to nil,

not just object types.

Implicitly Unwrapped Optionals

As described above, optionals

indicate that a constant or variable is allowed to have “no value”. Optionals

can be checked with an if statement to see if a value exists, and can be conditionally

unwrapped with optional binding to access the optional’s value if it does

exist.

Sometimes it is clear from a

program’s structure that an optional will always have a value, after that value

is first set. In these cases, it is useful to remove the need to check and

unwrap the optional’s value every time it is accessed, because it can be safely

assumed to have a value all of the time.

These kinds of optionals are defined as

implicitly unwrapped optionals. You write an implicitly unwrapped optional by

placing an exclamation mark (String!) rather than a question mark (String?) after the type that you want to make optional.

Implicitly unwrapped optionals are

useful when an optional’s value is confirmed to exist immediately after the

optional is first defined and can definitely be assumed to exist at every point

thereafter. The primary use of implicitly unwrapped optionals in Swift is

during class initialization, as described in Unowned References and

Implicitly Unwrapped Optional Properties.

An implicitly unwrapped optional is a normal optional

behind the scenes, but can also be used like a nonoptional value, without the

need to unwrap the optional value each time it is accessed. The following

example shows the difference in behavior between an optional String and an implicitly unwrapped optional

String:

let

possibleString: String? = "An

optional string." println(possibleString!) //

requires an exclamation mark to access its value // prints "An optional

string."

let assumedString:

String! = "An

implicitly unwrapped optional string." println(assumedString) //

no exclamation mark is needed to access its value

// prints

"An implicitly unwrapped optional string."

You can think of an implicitly unwrapped optional as

giving permission for the optional to be unwrapped automatically whenever it is

used. Rather than placing an exclamation mark after the optional’s name each

time you use it, you place an exclamation mark after the optional’s type when

you declare it.

NOTE

If you try to access an implicitly

unwrapped optional when it does not contain a value, you will trigger a runtime

error. The result is exactly the same as if you place an exclamation mark after

a normal optional that does not contain a value.

You can still treat an implicitly

unwrapped optional like a normal optional, to check if it contains a value:

if

assumedString {

println(assumedString)

}

// prints "An implicitly unwrapped

optional string."

You can also use an implicitly

unwrapped optional with optional binding, to check and unwrap its value in a

single statement:

if

let definiteString

= assumedString { println(definiteString)

}

// prints

"An implicitly unwrapped optional string."

NOTE

Implicitly unwrapped optionals

should not be used when there is a possibility of a variable becoming nil at a later point. Always use a normal optional type

if you need to check for a nil

value during the lifetime of a variable.

Assertions

Optionals enable you to check for values

that may or may not exist, and to write code that copes gracefully with the

absence of a value. In some cases, however, it is simply not possible for your

code to continue execution if a value does not exist, or if a provided value

does not satisfy certain conditions. In these situations, you can trigger an

assertion in your code to end code execution and to provide an opportunity to

debug the cause of the absent or invalid value.

Debugging with Assertions

An assertion is a runtime check that

a logical condition definitely evaluates to true.

Literally put, an assertion

“asserts” that a condition is true. You use an assertion to make sure that an

essential condition is satisfied before executing any further code. If the

condition evaluates to true, code execution continues as usual; if the condition evaluates to false, code execution ends, and your app is

terminated.

If your code triggers an assertion

while running in a debug environment, such as when you build and run an app in

Xcode, you can see exactly where the invalid state occurred and query the state

of your app at the time that the assertion was triggered. An assertion also

lets you provide a suitable debug message as to the nature of the assert.

You write an assertion by calling

the global assert function.

You pass the assert function an

expression that evaluates to true or false and a message

that should be displayed if the result of the condition is false:

let

age = -3

assert(age

>= 0, "A

person's age cannot be less than zero")

// this causes

the assertion to trigger, because age is not >= 0

In this example, code execution will

continue only if age >= 0

evaluates to true, that is, if

the value of age is

non-negative. If the value of age is negative, as in the code above, then age

>= 0 evaluates to false, and the assertion is triggered, terminating the application.

Assertion messages cannot use

string interpolation. The assertion message can be omitted if desired, as in

the following example:

assert(age >= 0)

When to Use Assertions

Use an assertion whenever a

condition has the potential to be false, but must definitely be true in order

for your code to continue execution. Suitable scenarios for an assertion check

include:

See also Subscripts and Functions.

NOTE

Assertions

cause your app to terminate and are not a substitute for designing your code in

such a way that invalid conditions are unlikely to arise. Nonetheless, in

situations where invalid conditions are possible, an assertion is an effective

way to ensure that such conditions are highlighted and noticed during

development,

|

before your app is published.

|

Basic Operators

An operator is a special symbol or phrase that you use

to check, change, or combine values. For example, the addition operator (+) adds two numbers together (as in let i = 1 + 2). More complex examples

include the logical AND operator && (as in if enteredDoorCode &&

passedRetinaScan) and the increment operator ++i, which is a shortcut to increase the

value of i by 1.

Swift supports most standard C

operators and improves several capabilities to eliminate common coding errors.

The assignment operator (=) does not return a value, to prevent it from being mistakenly used

when the equal to operator (==) is intended. Arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /, % and so forth)

detect and disallow value overflow, to avoid unexpected results when working

with numbers that become larger or smaller than the allowed value range of the

type that stores them. You can opt in to value overflow behavior by using

Swift’s overflow operators, as described in Overflow Operators.

Unlike C, Swift lets you perform remainder (%) calculations on floating-point numbers.

Swift also provides two range operators (a..b and a...b) not found in

C, as a shortcut for expressing a range of values.

This chapter describes the common

operators in Swift. Advanced Operators covers

Swift’s advanced operators, and describes how to define your own custom

operators and implement the standard operators for your own custom types.

Terminology

Operators are unary, binary, or

ternary:

Unary operators operate on a single

target (such as -a). Unary prefix

operators appear immediately before their target (such as !b), and unary postfix operators appear